Notre ignorance et notre arrogance : “nous ne comprenons pas les intelligences qui nous entourent”. Animaux, plantes et machines...

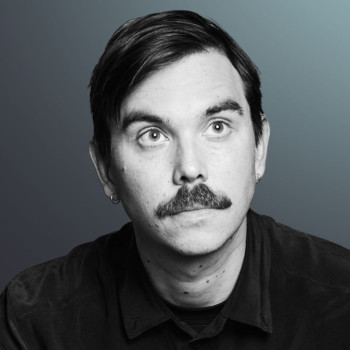

James Bridle est un auteur, artiste et penseur de la technique dont le travail porte essentiellement sur les liens entre la technologie, cognition et société.

Cette conversation est en lien avec son sujet de recherche et je suis appuyé sur son dernier livre « Toutes les intelligences du monde »pour préparer l’interview.

James nous invite à questionner la manière dont nous définissons l’intelligence et à nous rendre compte que nous ne comprenons quasiment rien à l’intelligence du monde vivant qui nous entoure. Pour lui, le développement des technologies numériques, des réseaux et des IA est l’occasion d’imaginer que d’autres formes de communications et d’intelligences sont possibles et que nous ferions bien de nous intéresser de plus près à toutes celles qui nous entourent déjà.

Personnellement j’ai beaucoup aimé cette conversation qui m’a fait prendre du recul sur l’arrogance des humains envers les autres formes de vie et aussi envers nos ancêtres. En extrapolant, on peut imaginer que ce sentiment de supériorité nous permet de justifier plus ou moins consciemment la destruction ou l’exploitation de tous ce qui n’est pas nous.

On parle de plantes qui entendent et mémorisent, de poulpe qui s’évade, du réseau secret des forêts, de la difficulté à délimiter notre propre personne, du langage comme limite à la compréhension de la complexité du monde, des origines animales de l’alphabet, de surprenantes découvertes archéologiques, de mise en réseau, des développements inexplorés de l’IA, d’IA en tant qu’ouverture vers d’autres formes d’intelligences, des pistes de changement de paradigme à grande échelle.

00:00 Introduction

03:39 Émergence de Nouvelles Formes d'Intelligence

07:47 Définition de l'Intelligence

10:43 Évolution de l'Intelligence et l'exception humaine

13:34 Variations Culturelles dans la Définition de l'Intelligence

17:22 Défis dans la Compréhension de l'Intelligence dans la Nature

20:19 Poulpes et Intelligence

27:37 Évolution et Égalité

29:09 Langage et Séparation du Monde

48:34 La Complexité de la Communication

55:37 Les Capacités Étonnantes de l'IA

57:28 Déterminisme Technologique et Pouvoir

01:06:43 Le Pouvoir et l'Impact des Corporations

01:10:07 Faire Face à la Complexité

01:13:53 Reconnexion avec d'Autres Formes d'Intelligence

01:17:55 Accès à une Conscience Différente

01:20:27 Livres Recommandés

Julien: Hello James.

James Bridle: Hi there.

Julien: So we will talk about how our perception of intelligence shapes our relationship with the world around us, and about other forms of intelligence on Earth, and about new sorts of intelligence that we have been busy creating for decades now, like artificial intelligence that we call artificial. So it's a broad and fascinating topic, and you've dedicated a book to it titled Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines, and the Search for Planetary Intelligence, and now it's available in French for the French speakers listening.

To start with, can you introduce yourself and tell me about your background, and how you would describe the lenses that you're using when you look at the world in our times?

James Bridle: Yeah, so I have sort of a number of backgrounds. I have a background academically, a long time ago, as a computer scientist, but also specialising in artificial intelligence in the kind of last wave of AI. So before the current big hype, the last time it got slightly hyped and then disappeared again, that was when I was working more in it, studying it.

And then I've worked in publishing, and I've worked on the web and various other places, and for the last decade or more I've mostly practised as a writer and as an artist, looking at how, broadly, the ways in which we understand the things around us shape our lives.

For a long time that was mostly concerned with technology, particularly the internet, and the way in which not just how new technologies, network technologies, shape our lives, but how our understanding of those things shapes our lives. So the extent to which we actually understand how the things around us work really matters to how they actually affect us.

And I've written and made quite a lot of work about the internet and other contemporary technologies in various ways, and in the last few years, in response to, fairly obviously, the situation we find ourselves in at present ecologically, I've been shifting my practice towards an ecological framework, but also trying to work out what I can bring from my thinking about technology, and how I've understood the relationship between technology, politics, society, to bear on ecological questions.

And the result of that is this new book, Ways of Being, where I really try to expand some of these ideas from being quite narrow technological ideas, ones that are often really just framed by the people in power or the people who work in tech companies and so on and so forth, and put them into a bit more context and bring them into dialogue with other ideas.

Julien: Yeah. So I think we can have a second interview related to your previous work on the internet, because it's also a fascinating topic, but today I want to focus on that latest book.

This is something I heard you mentioning, and we can go back to this later, but I have the feeling that we are at a very special point in history, and it's very strange, because we are starting to see emerge a new form of what we call intelligence, that we call AI, and that keeps surprising us, and at the same time we start to realise that there are plenty of forms of intelligence in nature that we can observe and that we don't really understand.

Is it one of the reasons why you wrote this book? And I would like to understand better why the matter of intelligence matters so much now, according to you. Why is it such an important topic?

James Bridle: I mean, that's kind of why I wrote this, or got interested in it, because I found it so extraordinarily fascinating that we seem so obsessed with this idea, because it's really one of the central questions, I think, of our time.

It just became very evident to me that there was this sort of strange coming together, as you say, of these two areas of interest that weren't being well connected but seemed to be very present.

On the one hand, we're starting to see very powerful computer systems, and we could have a discussion about what we actually mean when we say "AI", but let's just say very powerful computer systems that do very clever things, that on one side get this label "AI" that gets us very excited.

On the other hand, there's a growing pressure from various directions, both from scientific research into animal behaviourism, from ecological relationships, but also from non-Western systems of knowledge, from indigenous knowledge systems that have always recognised the intelligence of other beings, to reorient our relationship towards other species at a time of planetary crisis.

When, obviously, or it seems to me, so many of our current problems, so much of the pressure pushing us towards quite bad planetary outcomes, comes out of our bad relationships with other species.

So the fact that we can manage to hold these two things at once is really interesting to me: on the one hand, this intelligence, possibly emerging but in fact ever-present, starting to be recognised in the rest of the planet, and on the other hand this kind of weird toy intelligence that we're building ourselves, that comes with all of this mythological weight, all of this weight of science-fiction films, all of this priming for what we might expect, and that strikes at something so fundamental to being human.

Which is this real idea that AI, whatever it is, is somehow some sort of competition to us, or some kind of threat to us. It triggers us in all these ways, because our intelligence is one of the things that makes us think we're special, that makes us think we're this kind of unique species.

And so suddenly, having spent centuries, and in different cultures, separating ourselves from other forms of intelligence in order to convince ourselves that we're better, and that we can take advantage of other species, suddenly the call is coming from inside the house. We've made these little boxes that also have this weird way of speaking to us, and it produces a whole bunch of very strange psychological effects, and it's absolutely fascinating to look at.

Julien: Yes. And actually I want to divide the conversation in two. First talk about intelligence, and what is related to intelligence in nature in your book, that we understand, and then we can talk about AI and try to regroup everything as a whole, because this is what I do broadly usually: I try to define the terms of the conversation. And here we have a very interesting term to define, which is "intelligence".

What is it, and what would you say is our common understanding or common definition of intelligence, and is it a good one?

James Bridle: So I'll start by saying that I don't tend to try and define terms. In fact, I think that's quite often part of the problem, and that historically part of the problem has been that we've tried to find these really fixed definitions for things, and then we've stuck to them despite all of the stuff that gets excluded or left out, or kind of actively erased by that process of definition-making.

You can see it very clearly in the history of our ideas about what constitutes intelligence. When I set out to write this book, I assumed that somewhere I would find the real definition of intelligence that people used, even just in an academic context or whatever it is. I thought somewhere there would be: okay, this is what we say intelligence is, and here we go.

That doesn't really exist. Intelligence is not a concept that is that rigorously defined. It's very rigorously defined within very narrow boundaries in certain disciplines, but really what we mean when we say, when you hear people talk about intelligence in general, whether it's people talking about artificial intelligence or talking about smart people, whatever it is, what they mean is "what humans do".

There's a whole grab-bag of different things: planning, memory, thinking ahead, face recognition, any of these qualities that involve some kind of mental processing and interacting with the world. But as soon as you bring in that term "intelligence", it comes with a whole bunch of assumptions about who’s doing that thinking and how they're doing that thinking.

And so when the term gets narrowed down, it's mostly in this exclusionary way. We say something is intelligent, and we've been doing this to AI and to non-humans for a very long time, drawing these totally arbitrary lines between the kinds of thinking that we accept as being "intelligent", as though it's some kind of weird and exclusive club.

What I'm mostly interested in doing is actually expanding that definition, to see what we can include within it in a much broader array, and then seeing what happens when you do that. How do you respond? How do you have different kinds of relationships when you start to accept or see things as being intelligent, rather than trying to gate-keep that definition?

Julien: And did you find that how we define intelligence through time has evolved, and has it shaped our relationship with the world around us and the living world around us?

Would you say that the way we define intelligence in a specific culture has a role in how it's shaping our relationship with the living world around us?

Some say that, for example, the fact that we start to consider human beings different from the other species has a huge influence on how civilisation has taken shape. How would you describe that relationship, and its evolution through time and across different cultures?

James Bridle: Well, I mean, I'm not a specific historian in this, but it's fairly clear that there are differences within different cultures in the degree to which we acknowledge not just the intelligence but the agency, consciousness, being-hood of other species.

In Western culture that has a very long cultural history, and it goes back to monotheistic religions. You know, in the Bible it's written that God gives all the plants and the animals to man for his use, and that's been used for millennia to justify human exploitation of other species.

More recently, the scientific Enlightenment in Europe really reduced beasts to the status of machines. The Cartesian idea of consciousness completely excluded non-humans. Descartes performed horrific experiments on animals because he didn't believe they had souls or consciousness or any kind of awareness.

That belief has created not just a system of human exceptionalism, but a vastly abusive regime of mass agriculture that we have in the present, the slaughter of millions of animals every day under horrifying conditions, and the ecological damage from that as well.

And further ecological damage, where we see the whole world as a resource for extraction. It even has a relationship to our relationship to other human beings. Historians have shown the ways in which cultures which exploited animals and developed agriculture along certain lines also went on to exploit other human beings. There's a relationship between the abuse of animals and slave-keeping, and to gender inequality, these kinds of things.

So really our relationship with other species is part of a continuum with a whole bunch of other issues that we have relating to one another, to creatures, and to the planet.

But it is also one that's, as you say, really highly variable, and as in most things, it's been taken to its most extreme in the West under the dominant science. But many, many cultures have preserved a relationship that isn't just in better harmony with this kind of ecological relation, but actually views other beings as having their own agency and being.

So much of what I write in the book about this supposedly wondrous "discovery" of intelligence amongst animals is completely obvious to very large numbers of people who have always grown up knowing that other creatures are intelligent, and as a result have very different societal and ecological relations.

Julien: What's also very interesting here is that, even if you say we don't have a precise definition of intelligence, it seems that every culture has its own way of looking at it and that this also influences how they will treat other people, other cultures, other animals.

You can see this through history, trying to rank cultures and trying to rank groups of people by looking down on them because they say, "they are dumb" or "they're dumber than us", or "we are more intelligent as people, and therefore we can treat them badly".

We can also look down on our ancestors, thinking that prehistoric humans were dumber, and we have actually new discoveries that challenge that view, that we're actually smarter than the people before us.

Can you tell a few words about this?

James Bridle: I don't know exactly which discovery you're referring to, but I mean there's certainly a number of them. In the book I mention the fact that we are rediscovering that, actually, before civilisation existed, humans were already very, very intelligent, and they had just a different way of being intelligent.

So this term "civilisation" starts to become a very questionable one, I think, at that moment. Perhaps to pick a couple of things I write about in the book: the discovery of Göbekli Tepe, which is an extraordinary archaeological site and was once a great temple in southern Anatolia, in what's now Turkey.

This is a site that's tens of thousands of years old, and basically, when it was discovered, it kind of upends our understanding of how what we call "civilisation" developed, because the prevailing theory had always been that humans only became capable of works of art, of architecture, of nuanced, complex culture, once we settled down and became farmers.

And that turns out not to be true, because this vast temple complex predates agriculture, and was clearly a place where people who we considered to be hunter-gatherers, which is again also a contested term these days, would gather for seasonal festivities. They quite clearly had really huge parties there, and they had a complex social life, religious orientation, all of these things, on completely different lines.

And, you know, it's not just our ancestors either. Neanderthal peoples, who are a separate branch of the evolutionary tree, although we are related to them and there was cross-breeding in various ways, they had their own culture that they evolved separately, like other human cultures have existed on the planet at different times, long, long before in fact Homo sapiens even appeared on the scene.

And culture is also critically not exclusive to human beings. Non-humans have culture as well, even if we don't necessarily recognise it as "civilisation". We recognise their ability to tell stories, to mourn, to make artefacts, to do these kinds of things that we recognise as cultural within humans.

So that very narrow timeline of "civilisation" that we've been taught for so long in the West really is fraying and coming apart with a lot of these realisations.

Julien: And I want to talk about the animals and the intelligence that we can find in nature, because your book is full of it. But to start with: what is the problem with our approach to understanding other living beings?

Is it because the tests and methods are wrong and we fail to see intelligence in them? Or is it because we tend to divide things into parts and classify into categories, as you mentioned, the fact that we want to define everything? Or is it because we are simply limited and there are things that we just will never understand?

James Bridle: Yeah, I mean, those are all good reasons. I think we should be careful about which "we" we are talking about here, because even within dominant science culture, historically I think there was a problem within scientific research, as within all areas of historical research, in the ways in which experiments were designed.

There are a lot of researchers out there who are much smarter than that, who are doing incredibly interesting, more complex things than perhaps a couple of the examples that I'll give in a moment. But it's always worth remembering that popular culture lags a long way behind scientific research most of the time, for a whole bunch of reasons we probably don't need to go into.

I think a lot about the fact that the discovery of relativity is now over a hundred years ago, but has barely entered culture. We still live with an entirely Newtonian culture, even though the science is in a totally different place that has quite radical implications for how we should understand the world.

And so a lot of our relationships with more-than-humans, and our understanding of things like species, which turns out to be very problematic, are really in a very different place in much research than they are in common understanding, which is really great for us to talk about and disseminate. So, you know, maybe that's okay.

But with regard to these questions of why we've struggled to recognise intelligence in other species, I think you're right that historically, because we've centred human intelligence, all of our tests, essentially, these experiments we've done on other beings, have been about whether they meet some of these arbitrary criteria.

And that leads to all kinds of particular problems with our ability to see their intelligence, first of all, because in that model they can only be intelligent in particular ways that we recognise as being intelligent. So we set them all these weird tests, like looking at themselves in the mirror and seeing if they recognise themselves, or using various tools, solving problems that are essentially problems for humans that aren't necessarily issues in their world.

The mirror test is a classic example, because a bunch of different animals behave very, very differently when shown in the mirror. Some primates, like us, react much like us: if they haven't seen a mirror before, they might be a bit freaked out at first, but after a bit of getting used to it they will look at themselves, they'll touch marks on their faces if something's been painted on their face, or they'll pull faces or whatever. They'll interact in this way and they seem to recognise themselves.

Except not always in the same way. Gorillas, weirdly, seem to be incredibly shy in front of mirrors, they don't like being seen. It might have something to do with the role of eye contact in their culture.

Macaque monkeys and rhesus monkeys, other smaller primates, tend to look at their genitals mostly rather than their faces, and that's what they do out in the wild as well. Again, there are issues around eye contact, dominance, sexual display, so they simply don't behave in front of a mirror in the same way.

When they first tried to do the mirror test on dolphins, the dolphins immediately just had a lot of sex in front of the mirrors. That's what they seemed to be interested in doing.

So if you do something as simple as look through the lens of this mirror test, which is endlessly fascinating but I think scientifically really quite rocky, you start to see these different ways in which intelligence manifests. There's something going on here that you really have to be quite hard-line not to recognise as an intelligent response, but it's a response that's radically different to our own.

I should also mention that the mirror test varies across cultures, and that white Europeans and people from other cultures don't necessarily pass or address this test in the same way. So there's variance across humans, let alone across other species.

But one of the real findings of this kind of stuff is that you start to understand that there are different ways of being intelligent, that intelligence is not a singular fixed quality inside the mind, but is something that is actually done, that is the result of relationships and encounters.

And that's one of the reasons also why it's sometimes hard to recognise, as you said, because while it's possible for us to imagine, perhaps a little bit, what it's like to be a monkey or an ape, perhaps a tiny bit, because at least we share four limbs and a head on top of our body and we walk around, it's kind of impossible to imagine what it's like to be a jellyfish, right? Or almost anything that lives in the sea.

Or a bird, even, though they may display intelligent behaviours; their minds and the environments in which they live, and their experiences, are so radically different from ours that this idea that we could construct their world in such a way that we could understand it starts to lose sense.

Julien: Yeah, this is what you say: intelligence is embodied. It really depends on the senses that we have, and our own perception as human beings is clearly not the same as other animals, and therefore…

And the environment in which we live, you mentioned the sea, and therefore we cannot fathom, we cannot imagine what it is to be an octopus, for example. And yet, and this is one of the examples you have in your book, because octopuses are amazing animals.

Contrary to apes, here's a species that has very few things in common with us, maybe some ancestor, you talk about a little worm, but it's really not the same type of heritage. And yet they show evidence, signs of intelligence, and even the kind of intelligence that we define as being close to humans: they can escape traps, they can understand really sophisticated things.

What are the learnings when it comes to an animal like an octopus displaying signs of intelligence that we can understand, actually, in some ways?

James Bridle: I mean, I guess the way you put it there, you've told some of the good stories about them already. It's a bit like Göbekli Tepe, right? It's a bit like that Turkish temple we discovered under a vast hill: it completely blows the timeline away, the way in which we've constructed so much of our ideas.

Because the image that we've been taught, handed down in the West for centuries, is of this slowly rising arc of many things, of progress, but also of evolutionary development of intelligence. And it's always this arc, or stairway, or tower, with humans at the top, that says we are unique, we are uniquely special, we are the most evolved thing of all, we sit at the peak of that.

When in fact, when you meet something like the octopus, it challenges our understanding of what it means to be at the top of some kind of staircase like that, because of its extraordinary capabilities.

In addition to the ones you mentioned, one of my favourite examples is that octopuses are capable of recognising individual humans. They have very good facial recognition. They've tested this by having two quite similar-looking people who work in a research laboratory wear the same clothing every day, but then treat the octopuses slightly differently: one of them would give it food, and the other one would basically poke it with a stick.

And after a week, the octopus would greet one and squirt water at the other one, consistently. It's pretty easy to establish. Now humans can't tell individual octopuses apart. I mean, maybe if you spent a lot of time in the same place, whatever, but we don't have "facial recognition octopuses". But octopuses are clearly capable of recognising us.

So already you have one quality in which they seem to be more advanced, in a kind of thinking, than us.

And yet what's really confounding about that is, because they live inside this radically different medium, they spend most of their time underwater, and yet they're capable of doing this work also up and out of the water. When they escape from their tanks, they run around, or they just skitter across the rocks; they can exist in a different medium again in ways that we can't.

And yet they only live for about two years, most of them. And this is a totally unsolved question: we don't really understand where octopus culture comes from, because there's some evidence of octopus culture in architecture, building, structure-building, this kind of stuff, and some kind of communities that have been found, but there's no way in which those get passed on generationally.

So it's a huge mystery. It's a kind of intelligence that is just so bizarre in so many ways, and we also don't really understand how it comes about or how it's passed down, in the way that we think culture is encoded intelligence that can be passed down generationally.

So there's all this mystery there, but mostly it just tells us that whatever this thing is we call "intelligence", and again I want to keep that term really as blurry as possible to keep it as interesting as possible, whatever we think that is, it's not something that's part of a hierarchical, upward-trending lineage.

It's something that's exploding out like a firework, with all these different variants of it happening all over the place, evolving in all these different ways.

And I said earlier that there's this illusion that humans are the most evolved things on the planet. I always come back to the words of the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, an extraordinary scholar. Her phrase is that "everything is equally evolved".

Everything on this planet, including us and the jellyfish and the octopus and the giraffe and the frog and the toad and whatever, we've all been evolving for the same length of time, since the very dawn of life on this planet. Nothing is more evolved than anything else, and each has found its own expression in the world as a result.

Julien: Well, I find this quote really amazing, because it's so insightful. It actually strikes me because it's something that we never think of, because we indeed tend to see ourselves as superior, as very different from any other species.

And indeed we are very different, but as you say, when you realise that you can define intelligence as being adapted to your environment, and you see all the species are very well adapted to their environment, when you realise that evolution has been the same for every living being on Earth, that every species has ancestors and millions of years of evolution and interaction with those species…

Can you elaborate on what it means, and what are the insights related to "we are equally evolved"? Because I find it very powerful.

James Bridle: I mean, for me the main understanding of that is that you just have to be humble towards this idea of human uniqueness. Humans are one particular expression of evolution, an endlessly fascinating one, and each individual, in any species, has its own unique experience of the world and its own unique expression of that.

But we're not unique in terms of our experience of the world. We all share and experience this world in all of these different ways.

What I'm always fascinated by, and therefore looking for and trying to find all these times, are these little moments when you can imagine what that slightly larger shared world actually looks and feels like.

So with other humans we broadly understand what we share, we don't even think about it. We share the frequencies of light, and the audible range, and the tactility, the feeling of the world around us, and the architectures we build out of that and so on. That is our shared world.

What is the world we share with plants, for example? Well, we share the sun, we share the feel of sunlight on the skin, we share, to some extent, the chemistry of the Earth, whether we're rooted in it or whether we drink the water that comes out of it or mine it or whatever. That's part of our shared experience of the Earth.

We discover more when we start looking. We now understand that plants hear. There were these extraordinary experiments done in Britain, I think at the University of Bristol a few years ago, where they took, I think, cabbage-white caterpillars, and they put them on the plant and they saw that when the caterpillars started eating, munching on the plant leaves, the plant immediately responded by putting these chemicals into the plant leaves.

Then they took the caterpillars away, and sometime later they just played the plant the sound of the caterpillars chewing on leaves, and immediately the plant responded in the same way with these chemicals. So plants can hear.

What are we even supposed to do with that information? To understand that the vegetation that surrounds us is also participating in the aural world in some way.

And further experiments have shown that plants, as you say, have forms of memory, that they can adapt to things that have happened to them in the past, they can recall that experience, change their behaviour. They communicate, they share resources.

They do so many of the things that we do, and when we do them we call them "intelligent". And so this world of awareness opens up.

It's not the only way of finding that kind of shared space; there are other ways of having that awareness, that consciousness even, that communication with plants. But it's amazing to see the science expand and the awareness expand that allows us to access that.

Julien: Very specifically, can we dwell a little bit on this? Because it's again very interesting to realise that science is discovering so many things, for example related to trees and how they communicate.

More and more, actually, we can even see a forest as one kind of living being, because it's such a complex network of things. And we can see also that plants can move geographically, they migrate.

Can you explain some of the amazing discoveries we have made on trees?

James Bridle: I mean, there's so much to say. It's not really my research, but I love talking about it and telling the stories.

The big revolution within this understanding of forest ecology is an ecological understanding, so it's worth trying to define that.

"Ecology" is one that's worth defining a little bit. Ecology simply means that things are in relationship with one another. It says that the relationships between different things, whether those are beings, whether those are ideas, whether those are scientific disciplines, that the thing that binds them and makes them alive and makes them interesting and makes them matter, in the sense of both being important and being present, is their relationships.

And it's extraordinary the way in which so many scientific disciplines in the last hundred years or so, and the concept of ecology itself is quite old now, but it's taken a long time for various different disciplines to discover this ecological possibility within their own discipline. Ecology isn't really a thing in itself, it's a way of thinking about the world.

And of course biology is one of the places in which this notion of ecology originates, in this slow realisation that forests are not just collections of beings, but really interwoven networks of them.

So the forest isn't just a collection of trees, but the trees are really dependent upon the whole entirety of the forest for their own being in various ways.

The discovery, in the 1970s and 1980s, of what are called the mycorrhizal networks, which are these networks of fungi that connect plant roots… I mean, they don't even just connect them, they literally grow into them, so the threads of the mycelium, of the fungal material, wind right into the root cells of the plants, and they carry nutrients at different times.

So in the summer, when the broadleaf trees, the deciduous trees, are sucking up all the sunlight, they're creating a lot of carbon, nitrogen, stuff like this. They send that into these ground networks, and it's taken up by some of the coniferous trees, the pines, things like this that thrive in the winter, so they can survive while they're in the shade.

Then, at the turn of the seasons, in the winter, that's reversed. The broadleaf trees drop their leaves, the pines start to get more of the sun, and to help feed this forest ecology, some of that goes back into the ground and is taken up by the trees that don't have their leaves at that time of year.

But it's more complicated than that still, because those trees have a preference for their kin. They have what are called "mother trees", which have been shown to send more of the nutrients to plants that they've seeded or that are closely related to them in some way. So even within the forest ecology, you have essentially families of trees that are supporting one another.

And then it's not just nutrients that are being transferred, but information as well, and this is still only beginning to be understood. For example, when a tree on one side of a forest is attacked by insects, it can send a signal out through this network and through pheromones transmitted through the air to warn other trees of this attack, and they'll start producing defences before the insects get there.

So the forest is this place that's completely alive with interconnection, transmission, this sharing, cooperation, and also chatter, this information being shared about its own state.

One of the things I think it does that's really interesting is that when you start to see that relationship, it starts to blur all of the boundaries we have between individual and group, between members of different species, between the whole idea that there are single reducible entities in the world. You can do that action as much with the human as with trees and plants.

Julien: Yeah, and this is astonishing, because again it's very counterintuitive. We see ourselves as individuals, you know, we have a body and we see "this is me", and we see humans as a separate species from the rest.

But what we realise more and more is that every living being depends on other species to exist, and our body, just to function, needs to be inhabited by millions of bacteria, for example.

We even find that our DNA has been modified not just by evolution, but by viruses. Again, can you elaborate on this? Because what is the meaning of that? Does it mean that we need to realise that everything is connected, and that it doesn't really make sense to separate species and isolate individuals? What are the doors that it opens up in terms of philosophy?

James Bridle: I mean, it's just… We were talking before about this idea of the tree of evolution, and even the most scientifically-minded of us, who are comfortable with the idea that we came from a lineage of primates and other apes, it starts to get weird when we start to think that we came from underneath bacteria as well, that we're descended from herpes, right? That that's one of the main bacterial ancestors that we have.

And that our ancestors take all these forms back throughout history, and that we come from this extraordinary lineage of all kinds of other strange creatures.

Also, I mentioned Lynn Margulis earlier. Her work was entirely focused on the fact that that history of evolution has been one, in large part, of synthesis and cooperation, rather than antagonism. It's not the Darwinian model that we've mostly been educated into for the last 150 years or so, which really stresses evolution as some kind of fight, essentially.

We come from a long line of beings coming into relationship with each other, and cooperating, working together, networking essentially, rather than trying to kill and eat each other. That's not the dominant aspect of our history.

So it allows us to really understand the potentiality of our relations in an entirely different way, that it can be one of mutual flourishing rather than one of eternal competition, which is largely what we share.

But yeah, as you say, it has this relevance at the bodily level as well. One of the most extraordinary things I think I learned writing the book is the extent to which we are not just the product of our ancestors directly, but of this extraordinary ongoing cross-breeding that occurs between different types of beings.

In fact, the uterus, the cradle of mammalian life, evolved not as the result of a series of traits being passed down from generation to generation, but as a viral infection. We actually were infected with the uterus, effectively – it's a little more complicated – through this process of horizontal gene transfer from another lineage.

Again, we keep coming back to this metaphor of the pillar or the tree of evolution, and every one of these things, earlier I said that this tree is less of a pillar and more of something spread out. We also have to understand it as something that's completely entangled and interwoven in all these ways as well, that there's really no up or down or separation. Everything is fractally connected in this way.

Then when you get down to the level of the individual, there's articles in scientific papers that are 20 years old now going, "Maybe we should discard the idea of the individual at all", because scientifically it's unclear where the body begins or ends.

We think of ourselves as a single species, a single individual, but we carry around about two kilograms of very distinct other genetic species in our gut and on our skin, these microbacteria and so on.

They're not just passengers, we have an ongoing relationship with them. One of the ways in which science has started to consider this, what we might replace the individual with, is we might almost replace it with this immune system, this networked collection of beings that together respond to the outside in some way.

They've shown that changing who lives in your gut changes who you are. Your brain behaves differently depending on the different little creatures that are also living in your body.

So who are you, right? Who am I, if I am both a compound of the "I" that I think I am, and all these other little "I"s that make me up?

We're far more complex creatures than we're even capable of thinking about on a day-to-day basis. No one wants to go around constantly thinking about every single bit of gut bacteria, but when we're thinking about how we relate to the world and how we understand it, and the extent to which we should break it down or draw these divisions, we should know that those division lines run right through our own bodies, and they're really quite theoretically unsustainable.

Julien: I mean, it opens up so many things, and we need ten hours to go through that. But I would like to talk about language a little bit, because it's often said that sophisticated language is what sets us apart from other living beings.

Usually we say it in a positive way, as if our way of communicating puts us above other species and makes us more intelligent. Interestingly, you argue that this is also what separates us from the world, what prevents us from understanding better how things really work.

Can you elaborate a little bit on language in general?

James Bridle: Yeah. I mean, it's like the looking-in-the-mirror thing, right? We put so much primacy on this thing that we do so well that we've taken it to be the be-all and end-all of intelligence.

Language is marvellous and extraordinary, it's a huge part of being human – that sounds kind of glib, but I mean it's part of what makes us human at a deep biological level: the structuring of our brains, the structuring of our lungs.

The language that we produce is embodied, because the languages that we speak are the result of our musculature, of the shape of our rib cages, of the structure of our throats. Ultimately, some of the things that we express are the result of being physically like this.

Which is just to say that language is not some abstract thing that separates us from the world in the sense that it makes us rise above it. Because I think that's partly what you're expressing: that we put language, or the ability to speak and read and write, onto this pedestal that makes us "better", when of course it's a function of the world.

It's a function of being in the world, breathing in and out, and the origins of language, much debated, emerge from the world itself. There are a lot of arguments that the noises that we make emerged as a result of speaking to one another, of listening to the sounds of animals and birds, of imitating them, of having these relationships with the world.

And that survives in very interesting ways. In the book I wrote quite a lot about the work of the philosopher David Abram, who talks about the fact that some of that relationship to the world was lost when we started writing things down. Because instead of being spoken interactions with the world that point directly to it, they become abstracted into language.

But he writes really beautifully about the fact that some of the world survives even in our written languages today. That the letter A comes from the Hebrew aleph, which comes from a Phoenician character that was originally a bull's head. If you turn a capital A upside down, you're looking at a little bull with its horn sticking up.

Or the letter M, it comes from again the Hebrew mem, and a Phoenician character before that that meant "water", so it's the flowing waves. Or the Q, with its little monkey tail, is what that originally signifies. These little aspects of them survive.

But there's so much interesting to be done with language, and there's so much that it lacks. In becoming linguistic beings in such a strong way, we tend to ignore a lot of the non-linguistic connection we have with the world, the world of experience, the world of the senses, of direct exposure that isn't bound around with the labels that we impose on things as soon as they come into language.

That's a whole much bigger subject. But it's also worth mentioning that we are really not unique in language. Many, many other creatures on the planet have languages, some of which we're starting to recognise in all kinds of strange places.

Weirdly, one of the best-explored languages at the moment is prairie dog. You know, those weird little fluffy creatures that live in little burrows on the prairies. They have a highly developed language. They can put sentences together. They have words to describe different creatures like "bird", "person", but they can also go "person blue-shirt". They can describe and they differentiate between people coming from different directions and the clothes they're wearing.

We've cracked this little tiny bit of their language, it's unbelievably fascinating. I really think it's very obvious that all animals have some form of communication, if it's pheromones, if it's whatever communication passes between creatures, even if it doesn't do it in the verbal structure that we understand to be language.

There's a lot of interest at the moment…

Julien: Yeah, you can keep going, because I guess communication is everywhere, we just fail to understand how it works most of the time.

James Bridle: And, you know, a lot of it, like we said before about animal behaviour, we may not be capable of understanding. And we have to be okay with that.

But we also have to be okay with the fact that our inability to understand those different forms of communication doesn't make them lesser, it just reveals our own inability to understand.

Julien: Well, I would like to jump to another language that we have created, made of zeros and ones, a digital language that has led us to do very surprising things, and to attempt to build a new type of what we call "intelligence", artificial intelligence.

That's another topic that you've been looking at a lot, and that's kind of your entry point, if I understand well: "Okay, what is happening now?"

First, what is the definition again? What is AI, why do we call it intelligence? It's a term that was coined first in 1956, I think, but it has evolved into something a bit confusing. What is the idea here?

James Bridle: Yeah, so, I mean, it's kind of boring and difficult to untangle exactly what we're talking about in this case, but AI is having such a bonkers moment it's maybe worth untangling a little bit. I agree.

I think the first thing to do is to differentiate between the AI, the idea of AI that we hear about so much, which essentially is computers that are smart, not just as smart as humans but smart like humans, and possibly more so in some way, at least in certain tasks – that's the idea of AI – and then we have actually existing AI, which is basically really fast, powerful computers doing statistics.

It's these things called neural networks, large language models, these technical terms, and I kind of wish we just used the technical terms, because as soon as you bring in this term "AI" you're bringing in the Terminator, that's where everyone's mind goes immediately, and so we're stuck with these big cultural metaphors.

The thing that I think is always really important to mention right now, at least, because there is this insane contemporary hype – and that's what it is – about actually existing AI, as though it's super-human AI, is that we're talking about a very… whatever artificial intelligence is, this thing that's being discussed at the moment is such a narrow version of what it might be.

We could go into that some more, but essentially what I mean is that the idea of AI, of computational, machine intelligence – let's maybe call it that for a little while, "machine intelligence" – has, as you say, been around since the 1950s, possibly even earlier, I'd say from Alan Turing's writings in the 1940s, possibly even earlier than that.

There have been a few ideas over the years about how it might be made. Back in the 50s and 60s there was a thing called "connectionism", which was the idea that if you just plugged enough wires and processes into each other you'd end up with something a bit like a brain, and that consciousness would just kind of emerge from that complexity, or at least intelligence if not consciousness.

Later on, when that didn't really work out, you got into things like expert systems, which were just these really complicated computer programs where they basically thought, "Look, if we just program all the rules of the world into this thing, even if it's just a small set of the world, like the business world, then maybe it'll be intelligent in that way." That didn't work at all, because the world is too complex to be put into all those little rules.

Ultimately, we kind of came back to connectionism in the form of neural networks, and neural networks are what's driving a lot of everything, which again is just loads and loads of powerful small computers all plugged into each other in complicated ways, doing a lot of statistical mathematics.

And I get into trouble for saying this quite a lot, but there has not been any major conceptual breakthrough in artificial intelligence for years. The reason that we have a massive hype bubble around AI at the moment is because we've had 20 years of a corporate-political situation where a few very large companies have made a huge amount of money out of advertising against our common information, and they've used that money to buy very expensive computers, and huge numbers of them, and accumulated so much data that you can train these systems.

Because what these systems need is: they need a lot of very powerful fast computers to process data, and a huge amount of data to learn from. And that's what Google and Facebook and Amazon and a couple of others have spent the last decade or more doing, gathering money and data to make this particular kind of computing possible.

And it is super impressive, it's weird, it's uncanny, it's a huge technical achievement. Is it "intelligent"? It depends how you define intelligence. I personally don't think that the ability to make money alone, or to beat other things, I don't think being the best competitor is necessarily the form of intelligence. But these are the qualities that this particular kind of AI we see in the present moment is developing towards, because of where it comes from.

Julien: Yeah, and that's also what's astonishing, because it's becoming so good at what it was designed for, which is to replicate human intelligence. And as you said, it's not coming from nowhere, and there is direction that is given to the way this is being developed.

But still, I would like to stay a little bit on this, because there was a lot of hype, especially this year, with ChatGPT and large language models starting to do things that are amazing to us, because they do things in appearance as if they were human, like being able to have a conversation, passing the Turing test, etc.

So just to understand a little bit what is happening this year: what is so astonishing about these new capabilities, and are you actually surprised by the speed of innovation in that field right now?

James Bridle: I mean, I don't think they're that amazing. I don't find a really good chatbot to be that spectacular.

Julien: No, but I mean, I'm saying this because just a year ago you were hearing interviews from people in that field who were telling us that an AI would never be able to do this and that, and just a few months later they…

James Bridle: I will never bet against powerful computers being something like… Of course, if you put the shared resources of five of the world's largest corporations, you hire all of the top academics of all the relevant disciplines – destroying a bunch of university departments in the process – and you focus these incredible resources on doing something, humans are pretty good at doing quite a lot of things.

But I really meant what I said. I don't think… ChatGPT or the image generation are amazing technical accomplishments, but are they that surprising? Are they that shocking? Are they that interesting? I'm not sure they are.

There are applications for this kind of statistical inference, neural modelling, large language modelling, that are super interesting, like the fact that things like protein folding, drug discovery, these large-scale data exploration tasks that humans aren't very good at, these things are really good at, and they're going to transform them.

And unfortunately, because of the people who are in charge, they're probably also going to transform a whole bunch of other stuff that they should stay the hell away from, like human relations and our kind of interest in forms of creativity and self-valuation. Here we are.

Julien: What do you think of technological determinism? I interviewed Kevin Kelly on that podcast, who is one of them, and wrote books like What Technology Wants and The Inevitable.

According to you – and you started to mention it – who and what is in control of the direction technology development takes right now?

James Bridle: I mean, with, I guess, all due respect to Kelly – he's done a huge amount of work in the area and I grew up reading Wired magazine and it in large part made me interested in the things that I'm interested in and where I am – that is the cheerleading for what might be called the Californian ideology, or has been called the Californian ideology by some.

Which is this idea of technological progress trumping everything, that technology itself has some kind of trajectory and we can't get in its way, and it will do whatever it wants and we just follow along and we live in its wake.

That's never been true, because people make technology, and people decide what technologies they make. That's the idea of technological determinism that you mentioned, that the future is entirely determined by the magical appearance of wondrous technologies, the like of which we have never seen before, and we must bow down to their needs and to the people who make technology and the people who sell it.

You see it in the present moment, when a whole bunch of executives from Silicon Valley can make this huge noise about the dangers of artificial intelligence – the thing that they're developing – and then get huge audiences with prime ministers and heads of state, and run these big AI summits, which I find to be extraordinary and quite baffling, because it's quite obvious where the actual problems are that we can't get enough attention drawn to.

But those are the people who are deciding what happens with this, because they are the ones, as I said, with the power and the money to make these kinds of technologies.

Technological determinism is a get-out clause for those people who can't or don't want to take responsibility for the things they're making in the world, because they're excited about the things they're building, and good for them, but they shouldn't perhaps have quite as much power to decide what happens to society more broadly.

Julien: And do you think we're in that moment where AI and what we're starting to develop is starting to be at a point where we don't understand how it works, really? Because you hear that sometimes, you heard some people at Facebook telling us, "We don't really understand how they come to that result," and what are the implications?

James Bridle: It's a really wonderful quality of them. I've worked with this myself in a project I write about in the book, where I trained my own self-driving car system.

I spent quite a lot of time trying to look inside it. What I really wanted to… There were several things I wanted to understand about that program. One of them was I wanted to understand how this machine saw the world.

Like I talked about earlier, how we share the world with plants and other creatures, we share the world with these, whatever they are. In this self-driving car project I really wanted to be able to look inside it in some way and really feel or see through its eyes.

And the blunt truth is, it's really hard to do, because the way in which machines perceive the world and store data about the world is just not readable by humans. They fundamentally construct their models of the world in ways that are completely illegible to humans.

In that case, I made a bunch of images that were kind of print-outs, representations of some of the data within the system, but they were models that I made back so that I could see. The thinking inside the machine is inscrutable.

There's a lovely article, I think in The New Yorker from probably five years ago now, maybe more, when Google first started using machine learning in Google Translate, and it suddenly made its language translation capabilities really powerful.

This journalist was embedded in their office and kept bothering the Google scientists to explain how the machine worked. He kept saying, "Can you just explain to me how these two words relate?" until basically one of the engineers kind of explodes at him and says, "I am not in the habit of trying to visualise multi-dimensional space."

Which is what it is. It's this vast array of data in weird relationships that makes no sense to the human mind.

So you can do some work around understanding how these systems basically function, but you can't understand how they think, because they think unlike human minds.

And that's really interesting, because it bothers, or it should bother, our sense of how we operate in the world, which is largely based on that kind of deep understanding.

But it should also perhaps prompt a re-evaluation of that view of the world, because of course we've lived around inscrutable intelligences the whole time, and we've refused to recognise them as intelligent.

We can't look inside the mind of a rabbit or a toad or a goldfish, because its model of the world, as we've said before, is so radically different to our own. And because it's so radically different, we've basically refused for so long to acknowledge that it has a model at all, that it has that intelligence, that consciousness.

What's brilliant about AI, really, for me, is that it punches through that. We have to acknowledge that this thing has a model of the world, that it has this agency, that it has this thing that's like intelligence, whatever it is.

And therefore human intelligence is not the only thing going, that there's more than one kind of intelligence, and if more than one then potentially infinite. Suddenly the world is filled with all of these different kinds of intelligences, in this beautiful way.

That, to me, is the real purpose of so much of our technologies.

We talked earlier about the structure of forests, the networks that exist between trees under the forest. When that research was first released in the journal Nature in the 1990s, the title they chose for the special issue of Nature when they published it was "Wood-wide webs", because it was just at a time when people, particularly academics, were starting to be connected to this thing that we now know as the World Wide Web and the internet.

So they had an idea of what networks were, based on their understanding of computer networks. Before we built computer networks, we didn't really understand what these kinds of networks looked like.

We subsequently realised, studying the internet, that we developed new kinds of mathematics which we then went and reapplied back to nature, in order to understand the forest networks better. It turned out that the forest networks follow certain kinds of mathematical topology in the same way that the internet does. They're not the same thing, but certain rules and metaphors apply.

I think about that a lot, that so many of the things that we make are attempts to remake things that exist already in nature, perhaps better in certain ways for our purposes, but really that are not novel at a universal scale, that evolution came up with most of this stuff a long time ago.

But because we're quite strange and solipsistic little creatures, we need to make them ourselves before we'll see them as real. For me, that's what AI is doing. We make these toy intelligences just so that we can really start to see a much broader idea of what intelligence is.

Julien: Well, that's a very positive way of looking at it, and to say, "Okay, this is what it's meant to do, to make us realise that there are other forms of intelligence."

But it's also very scary for me to imagine that we are creating something that is very powerful and that is developing very rapidly, and we don't really understand how it works or where it's going.

James Bridle: Well, that's politics for you. That's when this moves from being a technological question into a political question.

It becomes a question of power. Who is making these things? What are their intentions? How much power do they have over the rest of us? How much power of refusal do we have? Who shapes these things, and in whose interest?

Any technological question at sufficient scale is a political question, and it's one that requires far more of us to be involved in actively and with regard to our interests, just as the rest of our politics does.

Julien: I would like to talk about big challenges for humanity, and for years I've been trying to find good ways to explain our predicament, and the fact that as we grow and multiply and develop, we are consuming all the resources and killing most of the living beings, and deteriorating the conditions of life for the future, with climate change on top of it.

There is a great insight in the intro of your book related to how corporations work. You compare them to artificial intelligence, to the fact that actually it's already there, it's already acting as a program and doing some stuff that is running out of control.

Can you elaborate on this?

James Bridle: Yeah. I mean, it's a line or a joke from the science-fiction writer Charlie Stross, where he makes a very good point that artificial intelligence, real artificial intelligence, active artificial intelligence, out-of-control artificial intelligence, already exists in the world, and it's corporations.

Corporations are large autonomous entities who are capable of independent action, who have legal standing. They have legally protected speech, they can act in law, they can sue people and be sued, they can have private bank accounts, they can act in all the ways that people do, with none of the accountability to people that we have in normal human relationships.

That's why they're so damaging, because they remove a lot of the safeguards of what we might call civilised behaviour from human action and abstract it away. You get these vast, resource-hungry entities that have very narrow interests – profit and loss, that's really all they care about, not getting sued maybe – but that's how they define themselves, that's their little worldview of experience.

We already live with them, and they're already an incredibly huge, damaging thing to the planet. So when people talk about the dangers of AI, I think it's hilarious, because we already live in a place in which there are very large, powerful non-human entities damaging us and the world in very real ways, that we find very difficult to address.

So yeah, I was just putting AI into this special category of things, when, as I say, we really should be talking about who has power, where that power resides, rather than the narrow focus on technology, which is what they want us to do.

The current big AI safety debate is an attempt to redirect attention from wealth inequality, power inequalities, towards the development of software.

Julien: So we are facing extremely complex issues today, and we seem to be unable to really understand what is going on in many ways, and even more incapable of finding solutions.

In your view, what's your take on that, and are we able to deal with that level of complexity?

James Bridle: I go with Sven Lindqvist, the great Swedish writer. In his introduction to his extraordinary book Exterminate All the Brutes, he writes, "You already know enough. We all know enough already. The only thing is to decide to act."

I don't think there's any doubt in anyone's mind, really, on some deep level, of the situation that we're in. The IPCC reports, they're actual scientific reports from pretty much every scientific body on Earth. The US Army, the Chinese Communist Party, they all agree on this. They all point to a very serious trajectory for what's happening to us and the planet at the moment.

One of the things we're told over and over again is that it's too complicated. We're always being told, "This is too complex, it's really complex." It's not.

We're burning fossil fuels, increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, and that's leading to unsustainable heating that's going to render vast areas of the Earth uninhabitable in the next decades. And "uninhabitable" doesn't mean "uncomfortable", it means it'll kill you if you go there, or if you can't leave.

This is the level of emergency we're facing. At the same time we're facing the biodiversity crisis, wiping out all these species. This is all real.

I don't think the problem of addressing it is one of complexity, I think it's one of agency and power. On the one hand you have powerful interests who think this doesn't apply to them, and so they're not doing anything about it, or actively making the situation worse, which is the people who own the oil and gas companies, the people that they pay in government, and so on and so forth. It's not even a conspiracy, it's just the way things work.

On the other hand you have most of us, who have been trained into this learned helplessness in the face of these situations. I feel this very strongly, because I worked on this very specifically just within the narrow context of technology for so long, talking about the internet and the large algorithmic systems that it's generated, as things that make people feel helpless.

We know there's this vast structure going on, but we don't have any keys to get in there and address it or unlock it in any way, because we've been pretty much actively denied the skills for doing so. We've been educated into systems that haven't prepared us for this complexity of the world.

But complexity isn't a problem. The world is complex, and that complexity is brilliant, it's what gives rise to life itself. There's this belief that we need to conquer it in some way, that we need to "master" complexity, which is a dominating, colonial, imperial attitude at heart.

We don't, we just need to live better within that complexity, in better relation to the species around us.

And, to be very clear, we also know what needs to be done. We know what forms of democratic reorganisation will move us past the current impasse. We know about the kinds of technologies we need. We also know we need to change radically, that we can't continue on our current path, that degrowth is the only option for any kind of ongoing survival.

We know all those things. So the question to ask is not really "What should we do?", it's "What's stopping us from doing it in the present moment, and how do we shift that situation?"

Julien: And is there an answer to that related to how we inhabit the world, with the idea that we need to reconnect with the other forms of intelligence around us?

James Bridle: Yeah. I mean, I take multiple tracks on this. Part of that is forms of technological education and building agency in all kinds of ways. I do workshops where I teach people to code, and I do workshops where I teach people to build wooden structures. I think these are all valid forms of learning that build resilience in community and all these forms of power.

But a shift in consciousness is also required. We're not going to get to where we need to get to as a species, as a planet, without a real change in the way that we imagine things.

A big part of that is what we might term this animist reawakening, this return to some kind of consciousness that I fundamentally believe is inherent to life, as in I believe it's shared by all living beings. And by "living beings" I include things like rocks and some other stuff as well, so non-animate life.

What might be termed a planetary consciousness: it's real, it exists, you can access it, and many more of us need to be able to access it in order to make the kinds of changes that are necessary for our mutual flourishing and the survival of as many of us as possible, as to what's coming down the line.

Julien: To be clear, when you say – because we didn't talk much about consciousness, we talked about intelligence and consciousness is a very different topic – but how do you see things now, personally?

Is it like the big Gaia hypothesis, like James Lovelock, where everything is connected, everything is conscious in some ways? How did you get there?

James Bridle: That's one very good way of looking at it. It brings in the important qualities of emphasising a kind of feminine, regenerative energy. I would also refer to non-binary histories of that as well.

But I would refer largely to an energy field, or to an understanding of life that's more akin to the Einsteinian that we brought up earlier. Quantum physics tells us that what underlies reality is a shifting field of energies.

That's the same as is taught by the few remaining shamans of ancient Andean religions who live in far South America, who also teach animism and respect for all forms of life. It's the same understanding of the world that was taught by Buddhist practitioners in the East, and was brought to the West by people like Alan Watts, who said one of the most beautiful things I've ever heard, which is that "we do not come into the world, we come out of it like leaves on the tree or waves in the sea".

We are part of this world, and almost all of the damage that we've done to it and to one another can be attributed to us forgetting that. So remembering that connection is some of the most important work we can do, to at least begin to start on other paths of repair.

Julien: And that begins with experimenting things with your body, with silencing your thought… What are the things that people can take away and start?

James Bridle: I'm not about to start giving full advice on all that kind of stuff, but there are plenty of different paths to it. For me, long periods of study, thinking about the same kinds of things that are in the book, are one way of accessing it. So is fasting, meditating, hiking. All of these things are different doorways to activating a different kind of consciousness.

The primary one is opening oneself up to the world, listening to the creatures around you, and finding connections to them, however that is, whatever it is that works for you.

But I will say, I'm not trying to be esoteric about that, it's just that it's on the edge of language. We've talked for over an hour now about some of these practical, technical aspects, and when I start talking about a change in consciousness – and it's the reason I don't write about consciousness in the book – it's that consciousness is something beyond language.

It belongs to the realm of experience, and so it's something that's very hard to describe and speak about, because you immediately get bogged down into a bunch of stuff.

But I want to stress that it's very important to all the things that I've talked about, but it's not something that we can communicate in quite the way that we're talking today.

Julien: Interesting, yeah, it's not going through words – getting back to the topic of language.

So I have a couple of questions that I always ask at the end to my guests. When you look at the world today and its trajectory, what scares you the most, and what gives you hope, and maybe even joy?

James Bridle: I think I've been pretty clear about what scares me. The trajectory we're on is pretty serious, and I don't like the look of the future very often.

I worry about the future for future generations, and even for many people who are living now, and certainly for all the other creatures that we share the planet with.

What gives me hope is the capacity for change, always. We are endlessly capable of change. We have changed utterly throughout our evolutionary history, and even in recent history. These shifts are always possible, and they always seem to be completely unimaginable until suddenly they happen.

We are capable of changing in and ourselves, and we're capable of changing as wider societies.

I think the future is going to be really tough. That's not to say I think we're going to magically get through what's coming unscathed. It's going to be really bad at times, and I'm afraid of that, and we should all be afraid of that.

But that's not the same as being hopeless. So I work on practices that are meant to empower and engage people, and allow them to feel that they have a role to play in a world that's going to change very rapidly and in occasionally frightening ways, but it's still a world in which we can and will live and can affect and can change.

Julien: Last question, the toughest one: two books that everybody should read.

James Bridle: If you haven't read Braiding Sweetgrass, a novel by an Indigenous scientist who manages to weave these different practices together in such fascinating ways, then, you know, you should go and read that, because it will change the way you see and approach the world.

And yeah, since I mentioned him earlier, why not go and read some books by Alan Watts, who is one of the best people who explains what a different consciousness looks like to people who've been raised with a real absence of that awareness.

And if you don't read, there are tons of content through podcasts and videos, from these lectures.

Julien: Well, thank you so much for your time, James.

James Bridle: Thank you very much, it's been a pleasure.

Julien: Yeah, I will put the list on the website, as usual. Thank you very much.

James Bridle: Thank you so much.

Soutenez Sismique

Sismique existe grâce à ses donateurs.Aidez-moi à poursuivre cette enquête en toute indépendance.

Merci pour votre générosité ❤️

Nouveaux podcasts

Fierté Française. Au-delà du mythe d’un pays fragmenté

Comprendre le malaise démocratique français. Attachement, blessures et capacité d’agir

Les cycles du pouvoir

Comprendre la fatigue démocratique actuelle et ce vers quoi elle tend.

"L'ancien ordre ne reviendra pas"... Analyse du discours de Mark Carney à Davos

Diffusion et analyse d'un discours important du premier ministre du Canada

Écologie, justice sociale et classes populaires

Corps, territoires et violence invisible. Une autre discours sur l’écologie.

Opération Venezuela : le retour des empires

Opération Absolute Resolve, Trump et la fin de l’ordre libéral. Comprendre la nouvelle grammaire de la puissance à la suite de l'opération "Résolution absolue".

Vivant : l’étendue de notre ignorance et la magie des nouvelles découvertes

ADN environnemental : quand l'invisible laisse des traces et nous révèle un monde inconnu.

Les grands patrons et l'extrême droite. Enquête

Après la diabolisation : Patronat, médias, RN, cartographie d’une porosité

Géoconscience et poésie littorale

Dialogue entre science, imagination et art autour du pouvoir sensible des cartes