#92 - Interview

🇬🇧 Defining our times

Existential risks, propaganda, war, hope and the meaning of life : un des plus grands penseurs modernes nous explique sa vision des enjeux actuels

Écouter sur :

🇫🇷 fr

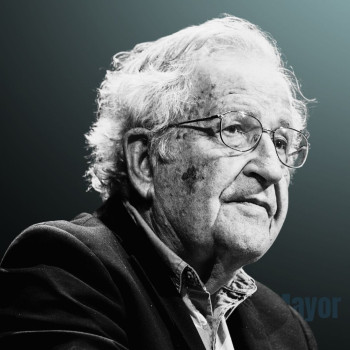

Noam Chomsky est une légende vivante. Il est considéré comme un des plus grands intellectuels de notre époque, tout simplement.

Il a fondé la linguistique générative, et ses théories sont devenues des références absolues dans le monde entier. Il a déclenché ce qu'on a coutume d'appeler « la révolution cognitive » et en tant que professeur émérite au MIT durant 60 ans son influence sur le monde académique a été immense.

Mais c'est surtout comme intellectuel engagé qu'il s'est rendu célèbre, avec ses prises de position opposées à la pensée dominante. En 1967, il publie "Responsabilités des intellectuels", un essai dans lequel il souligne l'importance de l'engagement politique des intellectuels en raison de leur capacité de discernement et de leur accès privilégié à la vérité. Ouvertement opposé à la guerre du Viêt Nam, Noam Chomsky prône la résistance face aux formes d'autorité illégitimes.

Il n’a eu de cesse de révéler au grand publique les techniques de propagandes utilisées par les Etats (son livre « la fabrication du consentement » est incontournable) et les puissants, et de condamner les abus de pouvoir de la puissance américaine.

A 93 ans, le professeur Chomsky continue d’écrire (il a publié plus de 100 ouvrages et des centaines d’articles) et de partager son point de vue éclairé sur le monde.

Ensemble nous parlons de sa vision de notre époque et de ses enjeux, des dynamiques et structures qui nous entrainent, de la guerre en Ukraine et du sens de la vie.

Julien Devaureix :

Hello, Professor Chomsky. It's really a pleasure to meet you and an honor to have you on this podcast. So, welcome.

Noam Chomsky :

Pleasure to be with you.

Julien Devaureix :

Your work is huge and you have published over 100 books on many different topics, so it's very difficult to know where to start. So let me try this.

Our planet is being reshaped by our global human civilization. The civilization is shaped by human behavior, and human behavior is conditioned by our nature, by our culture, by language and by all sorts of structures like the media, technology and politics. And so to understand how the world moves, what is in our hands collectively and individually, we need to talk about these structures, how they work, who controls them, etc.

Is it a good introduction to your work that covers language, geopolitics, and society? How do you like to look at things? How do you connect all the parts of your work together?

Noam Chomsky :

Well, first of all, I don't see any reason to try to unify them. There are many different interests. At some abstract level, they of course have links, but the particularities are what matter and the links fade into the background. They're not logical connections.

So, to be very abstract, there is a link that has been understood pretty well since the 17th century between language and freedom, essentially. If you go back to Galileo, Descartes, the Port-Royal grammarians and logicians at the Port-Royal Monastery, they recognized and were struck by the fact, they were amazed at the fact, that as they put it, with a small number of symbols we can construct infinitely many thoughts, and can even somehow convey to others, who have no access to our minds, the inner workings of our minds.

They regarded this as miraculous. For Descartes, this was the core argument for distinguishing res cogitans from res extensa, mind from matter. Galileo himself regarded the alphabet as the most spectacular of human inventions because it was able to record this amazing phenomena.

Wilhelm von Humboldt carried it forward to the next step. He said since the freedom to create thoughts and to use them and to transfer them is the essence of human nature, any form of restriction on freedom is illegitimate unless some justification can be given for it. It's the core of classical liberalism.

He was one of the great founders of classical liberalism. So all of this tied together. For Descartes, the crucial feature that distinguished humans from the rest of the organ-mechanical world was our ability to create freely in constructing and conveying thoughts in ways that are appropriate to situations but not compelled by them.

We're, as Cartesians put it, incited and inclined to speak in certain ways, but not compelled. So, right now, I'm not going to start talking about the weather outside because that would not be appropriate. But what I decide to say is freely chosen. That kind of creativity was taken to be the essence of human nature.

You find echoes of this in Rousseau and others. So at that level there is a connection between the version of classical liberalism that became anarchism in its modern variant. Illegitimate authority should not be tolerated because it constrains our fundamental capacities, which are revealed most strikingly and dramatically in the creation and conveying of thoughts.

So yes, there's an abstract connection, but it doesn't tell you that if you have this view of language you have to have that view of politics. They're not connected.

Julien Devaureix :

Yeah, sure. Well, thanks for explaining this and highlighting the fact that indeed sometimes it's difficult to connect everything together. And we will talk about many different topics today, because there are a lot of things that you're looking at, obviously.

I like to ask big questions. One of the reasons is because I think there is a value in seeing how people in general reframe these questions and narrow them down, because it tells something about how people think.

So one big question to start is: how would you define our times? Would you say that we are indeed living in a kind of special moment in history, and if so, what is so special about this?

Noam Chomsky :

Humans have been on the planet for a couple hundred thousand years, faced many challenges, overcome some of them, failed other times. Now is unique. This is the first time in human history, it will also be the last time, in which we have to answer the question: will the human experiment persist or is it facing an inglorious end?

That's the question of the time. We are right now at a time where we have to decide now whether organized human life on earth can continue, and that doesn't mean in the distant future. It means in the near future. The decisions we make now will determine that.

There are several [threats] that are so obvious that I hardly feel like repeating them. They should be on everyone's focus of attention. One is the warning that is given to us regularly now by the IPCC: we stop using fossil fuels now. Not “delay”, now. Cut back a certain percentage every year till within a couple of decades we've cut them out entirely. If we don't do that, we're essentially finished.

The other is the growing, severe threat of a nuclear war which will essentially wipe out everything. I mean, there'll be some stragglers, but the lucky ones will be those who die quickly. That's what we are now facing.

There's a third point. Actually, I'm quoting from the analysts who set the famous Doomsday Clock every January, minute hand set a certain distance from midnight, which means termination. They've been doing it for 75 years. During the Trump years they abandoned minutes, moved to seconds. It's now set at 100 seconds to midnight. Next January when it's reset, I wouldn't be surprised if it moves closer.

They mention three basic things. One is failure to deal with the drastic threat of heating the planet. That's one. Second is the growing threat of nuclear war. The third is the collapse and decline of an arena of rational discourse, sometimes called an infosphere. Can't talk rationally about things, have to scream and shout.

Well, that belongs, because unless we can approach these issues rationally, seriously, we have no hope of escape. So I think those are the three defining characteristics of our time, and it is very dire.

Julien Devaureix :

What would you say are the most important structures and dynamics that are defining that predicament, that human trajectory right now? And would you say that they are common to all societies?

Noam Chomsky :

The most important structure is, of course, in the wealthy societies. They are the ones who, like it or not, pretty much determine what the future will be. People in Africa can do things, but they can't have the influence that people in the United States or France or Germany have, or Russia. They are the ones who are going to determine [the outcome] because of their power.

Well, these are all basically state-capitalist powers. All of them, including Russia. Fundamentally capitalist institutions, with heavy state intervention, mostly for the benefit of the dominant owners and masters.

This goes back as far as Adam Smith, who laid out 250 years ago the basic structure of our institutions. He's famous for extolling the market, but that's not what he said. What he said is that the “masters of mankind”, his phrase, in his days that meant the merchants and manufacturers of England, said the masters of mankind are the principal architects of government policy, and they design it to ensure that their own interests are very well taken care of, however grievous the effect on the people of England, or worse, the victims of the savage injustice of the Europeans abroad.

He was concerned mainly with British crimes in India. Well, that's Adam Smith 250 years ago. The masters of the universe have changed. They're no longer the merchants and manufacturers of England. They're the great multinational corporations, mostly, but not entirely, based in the United States; huge financial institutions.

And they act very much the way the masters acted in Adam Smith's day. They largely control state power. They ensure that it works for their benefit, however grievous the effect on others, and right now even if they destroy the planet.

That's explicit, incidentally. I can virtually quote it. So a couple of days ago, right today, I read the New York Times front-page story. It's about how the Republican Party, which is the main supporter of private power — Democrats support it too, but not to that extreme extent — the Republican Party is now attacking businesses which claim to be taking into account climate change in their investment [decisions].

They're trying to pass laws to prevent a business from taking into account the effect on the climate, because we have to free business to destroy everything. That's called freedom. It's even called libertarianism. We have to free the masters, the owners, those who accumulate the core of capital. They have to be free to destroy the world as fast as they want.

That's the Republican Party. Democrats are not that extreme. Same in other countries. It happens to be more important in the United States because of its overwhelming power. But the institutions are pretty much ubiquitous. Some islands here and there, but not much.

Well, those are the fundamental institutions. They are suicidal. Capitalism is a death warrant. It's obvious. That's why business has refused to accept market principles. It has always called on a powerful state to intervene to protect it from the ravages of the market. Goes as far back as you want, very alive today.

So it's almost a joke today. The U.S. Treasury poured huge amounts of money to try to protect the financial institutions from the effects of the pandemic. For a fraction of what they spent, the U.S. government could buy the fossil fuel companies and turn them to renewable energy. A fraction of what was spent to bail out the financial institutions from one crisis, the pandemic crisis.

Well, that's how Adam Smith's principles work all over. Same in Europe. The business world, the masters, they understand that capitalism is a death warrant and they want to be saved from it, so they call in state power, which they largely control, to implement this for them. That's the fundamental structure of our society. If it continues, we're doomed, not in the distant future.

Julien Devaureix :

So one of the ways what you call, you know, the masters of the universe, the people that are in a situation of power and of potentially maintaining or changing the structures and the trajectories, one of the ways they have to exert their power is to use propaganda, to create stories and to try to manipulate people, to convince people to do certain things or to not do certain things.

Propaganda is something that you have been studying a lot. What is your take on propaganda and the influence that these people have on collective decisions and collective minds today? And how would you say it is different from 30 years ago, when you wrote Manufacturing Consent, for example?

Noam Chomsky :

Well, let's go back to the moment when the phrase “manufacturing consent” was created by Walter Lippmann, leading public intellectual of the 20th century, one of the founders of neoliberalism. The term “neoliberalism”, in fact, was coined at the Walter Lippmann Colloquium in Paris in 1938 to refer to the collection of doctrines that now dominate world society.

He was a Wilson-Roosevelt-Kennedy liberal, not a right-winger. He devised the phrase “manufacture of consent” and advised it as what he called a new art in the practice of democracy.

He said governments need, and power needs, manufacture of consent in order to keep the mass of the population just as what he called spectators, not participants. They are stupid, ignorant. We have to protect the responsible men — that's us — from what he called the trampling and rage of the bewildered herd.

The bewildered herd is the population. Have to suppress them, remove them from any influence. They have a role: they can push a button every couple of years to pick one of us to rule them, but that's it. That's liberal democratic theory. Liberal democratic theory, not just Lippmann. I could give you a whole host of others, Reinhold Niebuhr, all the icons of the liberal left, that's their view.

Well, he was relying on experience that he had in the first U.S. propaganda agency in the United States. It's called the Creel Commission, Commission on Public Information, which of course means public disinformation. That was set up by President Wilson to try to drive a pacifist population into wartime frenzy: hate everything German, Boston Symphony Orchestra can't play Beethoven, and so on.

That was necessary for Wilson. He was elected in 1916 on a peace platform called “peace without victory”. But he immediately turned it into “victory without peace”, and he had to change radically public opinion. So he set up this commission.

Walter Lippmann was one of the members. Another member was Edward Bernays, one of the main founders of the modern public relations industry. Both of them agreed what Bernays called “engineering of consent” is necessary to maintain control over the masses. The ignorant and stupid masses have to be marginalized.

Well, they both thought that the commission was very successful, and in fact it was: very quickly turned the population into raving anti-German hysterics. That was quite an achievement, and they were both impressed with it. Lippmann's phrase “manufacture of consent” my co-author Edward Herman and I picked up for our book Manufacturing Consent, but we're borrowing it from them.

Now, that's over a hundred years ago, and it was not just the United States, it was every country. The First World War is now far enough back so that we can think about it without hysteria. It is now recognized that the First World War had no purpose whatsoever. It was just mass slaughter out of stupidity and ignorance of the leadership. We don't have to argue that anymore.

But if you look back at the war in 1914, when the war began, in every country the intellectual classes overwhelmingly and enthusiastically supported the war, every single country. There's a famous manifesto of 93 German intellectuals appealing to the West, saying you have to support Germany, the country of Goethe, Kant, Beethoven, stands for civilization, join us to save civilization.

Same in England, same in France, same in the United States when the U.S. got into the war. All the same. The British had what they called a Ministry of Information, meaning disinformation, which was mainly used to try to convince American intellectuals to join the war effort by circulating fabricated stories about German atrocities, and so on.

It worked perfectly. There were a few people who didn't go along, like Bertrand Russell in England, was sent to jail. Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht in Germany, sent to jail. Eugene Debs in the United States, sent to jail. That was the pattern everywhere.

Well, that was over a century ago. Has it changed? Take a look at today. It's the same. In the United States, for example, there's a rule that you have to follow. Nobody articulated it, but it's understood by the intellectual classes: if you refer to Putin's criminal invasion of Ukraine, you have to call it the “unprovoked invasion of Ukraine”. If you check on Google, you'll [find] a million hits for that: “unprovoked invasion of Ukraine”.

Now do an experiment: look up “unprovoked invasion of Iraq”. Essentially nothing. A few hits from marginal people who opposed the war — somebody wrote a letter to the newspaper saying the war is wrong. So essentially nothing. There probably isn't a single statement by anyone anywhere near the mainstream who ever said “unprovoked invasion of Iraq”.

Well, that's a dramatic enough achievement of propaganda in itself. But it becomes even more so when we look at the facts. The facts are that the invasion of Iraq was totally unprovoked. There was no provocation whatsoever. And the invasion of Ukraine, there's no justification, but it is extensively provoked, openly and publicly. I won't run through the record.

So the intellectual classes have to say exactly the opposite of the truth, in unanimity, goose-stepping in repeating the slogans of the powerful state. Same happens in Russia, except there we ridicule it. When Russians uniformly say it's a “special military operation”, we ridicule this totalitarian state.

How about ourselves? Can't look at it. Actually, that's not entirely true. George Orwell is one of the few people who did look at it. I'm sure you've read Animal Farm. I'm pretty sure you haven't read the introduction to Animal Farm, because it wasn't published. It was withheld, was found 30 years later in his unpublished papers.

The introduction to Animal Farm is directed to the people of free England. And it says, “Don't feel too self-righteous. In England, unpopular ideas can be suppressed without the use of force.” Gives some examples. Couple of reasons. Says one of the reasons is a good education: you go to the right schools, you have instilled into you the understanding that there are certain things it wouldn't do to say, like “unprovoked invasion of Iraq”, wouldn't do to say that; there are other things that you must say, like “unprovoked invasion of Ukraine”.

And this goes across the board. This is one example. I can give thousands.

Well, how have things changed in the last century? Not at all. Have things changed since Adam Smith in terms of basic structures? A little, but not very much. These are deep-seated features of what we call civilization, Western society and culture.

I should say it's not worldwide. So if you read the Global South, they collapse in ridicule when they see [this]. They condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine. They say, “Yes, terrible crime, but what are you people talking about? This is what you do to us all the time. So stop moralizing.”

Julien Devaureix :

So you've been a clear critic of the U.S. policy since the 1960s, and I guess also this is because you have a way to understand how propaganda works, and you also have a point of view on geopolitics in general, of course.

Let's use the Russian-Ukrainian war to try to unpack all this, because that's a way also to talk about the nuclear risk that you mentioned in the beginning, a way to talk about your view on how the U.S. behaves internationally, the structure and the strategy that are there, and maybe also to continue talking about propaganda.

What's your view? What do you understand of this conflict, of what's going on, what's happening, and also where it is going potentially?

Noam Chomsky :

What's my view about the invasion, the reasons, and so on?

Julien Devaureix :

Yes. And the current situation and the role that the U.S. plays.

Noam Chomsky :

The role of the U.S. is essentially what it's been since the end of the Second World War, when the U.S. took over Britain's former role as the leading hegemonic power. Britain, of course, was no longer in a position to exercise that, became what the British Foreign Office called a “junior partner” of the United States, which took over the role of world control.

That's what the U.S. has played ever since. There have been some debates about this, particularly with regard to the status of Europe. Should Europe become an independent, what was called “third force” in international affairs, or should it be a vassal of the United States?

It's been a major issue in world affairs since the Second World War. The leading statesman who was an exponent of an independent Europe was, of course, Charles de Gaulle, who called for a Europe — in his phrase — “from the Atlantic to the Urals” with no military alliance.

Germany took a somewhat similar stance. That's what was called Ostpolitik, Willy Brandt and his successors: should move towards commercial, trade, cultural interactions with Russia. Gorbachev framed it very explicitly when the Soviet Union collapsed, said the post-Cold War world should be a “Common European Home” — his phrase — from Lisbon to Vladivostok, no military alliances, just commercial, cultural relations.

Actually, George H. W. Bush, first Bush, had a fairly similar position. It was called “Partnership for Peace”, in which NATO remained but as a marginal element. You could be part of the Partnership for Peace if you had nothing to do with NATO. Tajikistan joined. Actually there were some efforts from the Russian side to see if Russia could join.

That was the Gorbachev vision and to some extent the Bush vision. Bush was committed explicitly to the position that NATO would not expand — the phrase was “one inch to the east” of East Germany. That's as far as it would go.

Well, Clinton came into office. Within a couple of years, he was, as one of the leading U.S. ambassadors put it, talking from both sides of his mouth to Russia. He was saying, “Yeah, we're going to live up to the promise,” [but] to the ethnic groups inside the United States, like the Polish community, he was saying, “Don't worry, we'll incorporate you in NATO.”

By 1997 this became explicit. In fact, he told his friend Boris Yeltsin, “Please don't make too much of a fuss about our expanding NATO. I have to do it for domestic political reasons. I have to get the large ethnic vote, the Polish and other vote, in the urban centers. I just need this to win the election.”

Well, the next Bush, the second one, just opened the doors totally. Anybody can join NATO. Even Ukraine — made an offer to Ukraine to join NATO. France and Germany vetoed it, but given U.S. power, it remained on the agenda.

Jens Stoltenberg, the Secretary General of NATO, just a couple of weeks ago made a proud announcement that after the Maidan uprising in 2014, NATO, meaning the U.S., began pouring arms into Ukraine, joint military exercises, training of Ukrainian officers.

American diplomats understood perfectly well that this is what Russia called a “red line”, that they would not accept if Georgia and Ukraine, which are right in the heartland of Russian geostrategic concerns, joined a hostile military alliance. I mean, that would be as if Mexico joined a military alliance run by China, pouring Chinese weapons into Mexico, joint training missions, and so on.

If there was even a word about that, Mexico would be vaporized. It's not even thinkable. And if you look at it, you don't have to be a military genius to understand it. Just take a look at the map. Between Ukraine and Moscow there's no defensible borders. Operation Barbarossa went right through Ukraine all the way up to Moscow. Of course that, and the same with Georgia. And that was well understood, but it didn't matter.

In fact, the State Department has stated explicitly, in March shortly after the invasion, that the U.S. does not take into consideration Russian security concerns. It's not our business. We don't negotiate on those — meaning no negotiations, because negotiations, by definition, mean taking the opponent's concerns into consideration, even if you reject them. That's negotiations.

So no diplomacy, just war. And what it means is that under the U.S. lead, the West is carrying out a ghastly experiment. What they're doing is saying, “Let's keep the war going. We'll run an experiment. We'll see if Putin will slink away quietly in total defeat, or whether he'll use the weapons that of course he has to devastate Ukraine and set the stage for a terminal war.” That's Western policy.

In fact, it was made explicit a couple of weeks ago at the Ramstein military base in Germany. The United States called the NATO powers together at the military base and basically laid down the policy. The policy explicitly was to keep fighting the war to harm Russia, to make sure that Russia will never be able to carry out any offensive action, which basically means to destroy Russia. There's no other way to do it.

Basically the Versailles Treaty: destroy Germany so that it can never carry out military operations. Well, we see what that led to. Nice person named Hitler. But that's official policy. It's sometimes described as “fight Russia to the last Ukrainian”.

Maybe the Ukrainians favor this, that's their business. But we're talking about our policies. Our policies are: block negotiations, block diplomacy, and let's see how it turns out. If Ukraine gets devastated, we go to a terminal nuclear war — not our business. We pursue this policy.

I should say there's a split in NATO over this. If you take a look today, France, Macron; Germany, Scholz; Italy, Draghi have all made tentative proposals to try to establish a ceasefire and then move to some kind of diplomatic settlement. That's the European powers. The U.S. and Britain are strongly opposed, explicitly: no diplomacy, no ceasefire, continue with the ghastly experiment.

So there's a split in NATO, but the U.S. is so powerful that Europe basically goes along with it.

Julien Devaureix :

So we have a kind of trajectory, as you mentioned, that is happening because of certain behaviors and because of relationships between powerful people, powerful countries and the rest of the world.

When I hear you, it feels a little bit like things are locked into one direction. Is it the case? Is it that there is nothing that can be done to change that power game, or is there a kind of hope? And what needs to be done? What could change the situation, what could change the way the U.S. behaves and the direction of the things that you mentioned?

Noam Chomsky :

Sure, everything can be done. Just take a look at our situation. We're discussing this matter. Are the secret police coming into my study to arrest me and throw me into a concentration camp? Well, if we were doing it in Russia, that could be happening. We are not living in totalitarian states.

In Russia, there are dissidents, opponents of the war, very courageous, facing real problems. They may be thrown into prisons, concentration camps, killed. We don't face that. We can talk freely. We live in free, partially democratic societies.

We have a responsibility that people in other countries don't have because of our freedom and our power. This is where power lies. And luckily for us, enough struggles have been won over the centuries so that we have a substantial degree of freedom. Let's make use of it.

And there are people making use of it, mostly young people. It's the tragedy of today. It's young people who are the people of Extinction Rebellion, Sunrise Movement, others, who are demanding that the powerful use their capacity to overcome the crises that are going to destroy us.

So on the one hand you have, front page of the New York Times today, Republican Party, main party of business, trying to prevent businesses from taking climate into consideration in their investment decisions. On the other hand, you have young people out in the streets demanding that we do something about it. “We would like to survive. We would like our children to survive. Do something.”

When Greta Thunberg stands up at the Davos meeting and says, “You have betrayed us,” she's right. How did the rich and powerful respond? Pat on the head: “Nice little girl, why don't you go back to school and leave it to us?”

Well, if we're willing to accept that, we will march to catastrophe. But we don't have to. We don't have to accept it in nuclear war either.

You take a look at the powerful, the Hillary Clintons, leaders in Congress. They're at the verge of lunacy, literally. You have people there calling for a no-fly zone in Ukraine, calling for the U.S. military vessels to break the Russian blockade by sinking the Russian fleet.

Fortunately, there's a peace-keeping element inside the U.S. government. It's known as the Pentagon. So the Pentagon vetoes these proposals because they can think 30 seconds in advance. What does a no-fly zone mean? It means you have to control the air. How do you get control of the air? By destroying Russian anti-aircraft installations, which are within Russia.

So what you do is you bomb Russia and you hope Putin will say, “Gee, that was nice, why don't you do some more of it?” One possibility. Pentagon can think of another possibility.

Well, fortunately, for the moment, they're constraining the lunatics in the intellectual classes and political class. But for how long?

Julien Devaureix :

But that, I mean, because for tens of years activists have tried to change the trajectory and to change the rules of the game in many different ways. If you take, for example, climate change, which is a topic that you've looked into in depth, now we know what's going on, after years of denial, thanks to people fighting for information and against propaganda and lobbies.

But still the trajectory remains the same, and we fail to change the power games and to do anything serious about it. Is there something that we are missing in that game of influence, of trying to change power games and things? What could be done differently that would lead to different results, in your opinion?

Noam Chomsky :

First of all, we know the answers to that. Everything can be done. One thing that can be done is to remove, puncture, the thick veils of propaganda. That's one thing that can be done: talk about it, rational discourse, think about it. That can be done.

The second thing that could be done is to organize people, organize people to begin to act. Third thing is carry out the actions. There are many possibilities. All of this is completely open, can be very successful.

If we look at our own societies, they're much more civilized than they were 40 or 50 years ago. Things that were taken for granted back in the 50s and the 60s are just unspeakable today. That's progress. Not enough, but progress.

And there's a reaction to it, strong reaction against what's called “woke culture”, meaning minimal civilization, minimal civilized attitudes towards women, towards minorities, towards gays, others, minimal civilized attitudes; efforts to deal with global warming, that's “woke culture”, we’ve got to stop that.

So there's a backlash, but there's progress. Those are the means that work. They are open to us, available to us. The one thing that's missing is the will — the will to use the freedom that we have, the opportunities that we have, to carry us forward to a much better world.

All possible. The World Social Forum had its annual meeting a couple of weeks ago. They reiterated their slogan that “another world is possible”. Yes, it is. But you have to do something about it. Can't just go home and say, “I'll play some games on social media, or I'll go to a movie or something.” You have to do something about it.

It's open. People who have done it, often at great risk, have changed the world. Others can watch and look while the world goes up in flames, which is what's happening. We are now at a turning point in human history where we will either take action or we're finished. It's as simple as that.

Julien Devaureix :

So when you look into the future, what scares you the most? I think we get a little bit of the picture, but is there one of the things that we mentioned that you're really watching carefully? And on the contrary, do you see something in particular that really gives you hope?

Noam Chomsky :

Yes. All the things I've mentioned: the young people demanding that their elders, the ones with power, do something to save the world from destruction. In the case of Ukraine, pursue diplomacy instead of carrying out this grisly experiment of seeing if maybe Russia will concede total defeat and walk away — unlikely to happen and a hideous experiment.

So yes, accept the necessity for trying to move towards some kind of diplomatic settlement to terminate the horrors and lay the basis for further accommodation.

Talking about the climate crisis, we know exactly what has to be done. There are perfectly feasible means, easily within reach, that can mitigate and overcome it. With regard to nuclear weapons, even easier.

Here, incidentally, I should mention one of the incredible triumphs of propaganda. Let's look at the New York Times front page again today. Today's front page describes another Israeli attack on an Iranian nuclear facility. Israel is free to attack other countries at will, because it has U.S. backing and because of European cowardice. Europe cowers at the feet of the United States and says, “We're too cowardly to say anything.”

So the United States tells Israel, “You can do whatever you like.” Israel, rogue state, kills and assassinates and bombs whatever it wants. Well, that's described on the front page of the New York Times today favorably. Says, “Oh, good, Israel bombed the Iranian facility because of the threat…” — here comes the propaganda — “because of the threat of Iranian nuclear weapons.”

Well, let's admit for a moment that there is such a threat. There isn't, but let's admit it. Is there a way to deal with the threat? Yes. Very simple. Everyone knows it. No one is allowed to say it.

The way to deal with it is to establish a nuclear-weapons-free zone in the Middle East with intensive inspections, which can work. We know that from experience. So why don't we do it? Who's opposed to it? Iran is strongly in favor of it. Arab states have been strongly in favor of it for decades. The whole Global South is in favor of it, the G77, the Non-Aligned Movement. Europe is in favor of it.

What's stopping it? The U.S. vetoes it. Every time it comes up, the United States vetoes it, for a very simple reason: the U.S. does not want the Israeli nuclear arsenal to be inspected. In fact, the United States does not even formally recognize that Israel has nuclear weapons. Of course it does. Nobody doubts it, but [we] don't recognize it.

And there's a reason for that. If the U.S. recognizes that Israel has nuclear weapons, then U.S. law comes into play, which determines that U.S. aid to Israel is illegal under U.S. law. It's not observing the framework of the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

So why do we have to support Israel bombing Iranian nuclear installations, increasing the threat of war? Because we can't admit publicly that U.S. military aid to Israel — by far the leading recipient — is arguably illegal under U.S. law.

Can anybody say this? Yeah, I just said it. In fact, I've been saying it loudly for 20 years, but not in any way that can reach anywhere near public opinion. That's effective propaganda. That's what Orwell called controlling opinion, ensuring that unpopular ideas won't be expressed without the use of force.

This is perfectly simple. Any 10-year-old can understand it. But you just can't say it. One of those things it wouldn't do to say. You have a good education, you understand that. You're a columnist for the New York Times; you just have it internalized. The idea doesn't even come to mind.

That's our intellectual culture, what we call civilization. I just picked that example because it happens to be on the front pages today. I could have picked the same from a million others.

So what can we do? Everything. We can break the constraints of propaganda and we can move on to implement policies that'll lead to a much better world.

Julien Devaureix :

One last question, and a very easy one. What's the meaning of life according to you?

Noam Chomsky :

Very simple. The meaning of life is for each of us to answer. We have the gift of life for a short period on earth. We can decide what to make of it.

In the domain that we're understanding, we can decide, “I'll be a Soviet apparatchik. I'll conform to power. I'll obey. I'll repeat all the patriotic slogans.” That's one choice.

The other choice is to say, “No, I'm going to be the counterpart of a Russian dissident. I'm going to reject the propaganda. I'm going to condemn the crimes of state. I'm going to act to do something about them.”

We're much freer. We won't be punished for that. We’ll be punished maybe by vilification or condemnation or lies or something like that, but that's not like being sent to the Gulag. So we're free.

You want to be cowards? Free and easy. You want to try to lead to a better world? You can do it. Problems, difficulties, condemnation and hatred, but you're free to do it.

Well, that's the meaning of life in that particular domain. You can say the same thing about everything else, down to personal relations. We determine the meaning of life.

Julien Devaureix :

Professor Chomsky, thank you so much for your time.

Noam Chomsky :

Thank you.

Soutenez Sismique

Sismique existe grâce à ses donateurs.Aidez-moi à poursuivre cette enquête en toute indépendance.

Merci pour votre générosité ❤️

Nouveaux podcasts

Fierté Française. Au-delà du mythe d’un pays fragmenté

Comprendre le malaise démocratique français. Attachement, blessures et capacité d’agir

Les cycles du pouvoir

Comprendre la fatigue démocratique actuelle et ce vers quoi elle tend.

"L'ancien ordre ne reviendra pas"... Analyse du discours de Mark Carney à Davos

Diffusion et analyse d'un discours important du premier ministre du Canada

Écologie, justice sociale et classes populaires

Corps, territoires et violence invisible. Une autre discours sur l’écologie.

Opération Venezuela : le retour des empires

Opération Absolute Resolve, Trump et la fin de l’ordre libéral. Comprendre la nouvelle grammaire de la puissance à la suite de l'opération "Résolution absolue".

Vivant : l’étendue de notre ignorance et la magie des nouvelles découvertes

ADN environnemental : quand l'invisible laisse des traces et nous révèle un monde inconnu.

Les grands patrons et l'extrême droite. Enquête

Après la diabolisation : Patronat, médias, RN, cartographie d’une porosité

Géoconscience et poésie littorale

Dialogue entre science, imagination et art autour du pouvoir sensible des cartes